To Trill a Mockingbird

- Erin Keith, Esq.

- Sep 16, 2019

- 7 min read

Updated: Sep 17, 2019

The truth is, I’ve been dreading writing this post. Not because I didn’t have anything to say—I always have something to say. And not because I didn’t know the words to write; once I begin to type, the prose flows from my fingers, like water over pebbles in a gentle stream. No, the real reason I dreaded writing this post was because of the place within myself it would require me to go—the feelings it would require me to feel. I knew it would require a certain level of vulnerability—a willingness to take off a mask that I’ve been gripping onto for dear life.

And to be honest, that terrifies me as much as an adult as it did as a kid. Being called sensitive in the black community is closer to a slur than a compliment. It can be used as both a dismissive statement (read: “Girl, UGHH…you SO sensitive.") or as an insulting rhetorical inquisition (read: “D*mn girl, WHY you SO sensitive?"). But, let’s just say, in my 28 years, it’s rarely been a positive used to speak life into my gifts of empathy and compassion.

More often, it’s been a source of immense shame. I have literally prayed to God asking him why He created me to feel so deeply. Why He created me to care. Why He created me, a Black woman in America, without the standard order magical superpowers (read: survival skills) he’d given everyone else— the ability to suppress, and keep on keepin’ on, oh and certainly not cry in public.

As crazy as it sounds, there are times when I’ve literally begged God to make me numb, to remove the spirit of sensitivity from me, like it was an illness. I’ve prayed these prayers in the context of my public interest career, while trying my best to leave my clients’ very traumatic stories at the courthouse, rather than bringing them home with me to ruminate over a bottle of wine.

I’ve prayed these prayers in the context of my pockets, asking God why he couldn’t just let me enjoy corporate law, so I could have Louboutins and buy a home like most of my other lawyer friends, while also not feeling guilty like I’m abandoning a community that needs me. This one is truly easier said than done. “Let me know when you’re ready to make some real money,” is the most recent well-meaning one-liner that sent me to bed in tears.

I’ve prayed this prayer in the wake of my mounting student loan debt, while trying hard not to become helpless and hopeless.

And I’ve prayed this prayer in the context of the perpetual shootings of black and brown people by police, because no matter how much I want it to stop, my tears and my law degree, at times, seem similarly ineffective.

As I was going through some old boxes in my parents’ attic recently, I stumbled across a tattered copy of the novel To Kill a Mockingbird, that I read in my ninth grade English class. As I flipped through the yellowing pages, full of annotations, I went down memory lane. Reading over highlighted quotes in the book caused me to reflect on my journey, from being that sensitive high school girl who dreamed of becoming a writer and attorney, to the (still very sensitive) woman and advocate I am now.

For those of you who need a refresher, here’s a plot summary: A young girl, Scout Finch, her older brother, Jem Finch, and their father Atticus Finch, a prominent white lawyer, live in a sleepy Southern town. Scout and Jem try to make their own fun by snooping on Boo Radley, the neighborhood hermit who never leaves the house. Around this same time, Tom Robinson, a black man is accused of raping a white woman, Mayella Ewell, and Atticus decides to represent Tom, to the dismay of his white community.

Cutting right to the chase, Atticus proves Tom’s innocence, the all-white jury *shocker* convicts him anyway, and when Tom tries to escape from his wrongful jailing after the trial, he is shot to death. Angry that Atticus’ court performance has tarnished his family’s name, Mayella’s father, Mr. Ewell, attacks Jem and Scout on their way home from a Halloween party, while wielding a knife with which he injures Jem. Boo Radley emerges from the shadows where he was keeping a watchful eye on the children, and comes to their rescue, killing Mr. Ewell. The sheriff chooses to look the other way, agreeing that everyone will just say Mr. Ewell fell on his knife, because Boo is a gentle soul and was just trying to do the right thing.

Throughout the book, the central theme of the novel is made clear and affirmed over and over again: It is a sin to kill a mockingbird because mockingbirds are pure of spirit and it is the duty of all of ours to protect them.

The mockingbird symbolizes the ways the most innocent people among us, those with the softest dispositions and highly sensitive natures, are often persecuted when all they’re trying to do is go about their lives and spread love. It also symbolizes the way innocence of heart and mind can be stripped away, or killed, in an instant by the vileness of our world.

I remember finishing To Kill a Mockingbird and deciding that becoming an attorney like Atticus would be a noble goal. But I didn’t realize then how much I was more like Scout, gentle (but pretending to be tough), sensitive, and naïve about how dark evil can be. I remember the privilege I had with thinking that unjust endings like Tom Robinson’s, only happened during the Civil Rights Movement (e.g. Emmett Till), or in story books as a metaphoric literary device. I remember applying to law school, vowing to be a lawyer to help people and right the wrongs of our society. And I remember getting accepted, as an idealistic, optimistic, bright-eyed 21-year-old, promising to be the change I wished to see.

But then I hit law school and with heavy books and heavy reading came a heavy reality check. First, Trayvon Martin was murdered and his murderer didn’t pay. And then the following year, Michael Brown was shot and killed and his killer walked free. And then Sandra Bland wound up dead after what should’ve been a routine traffic stop. And then Eric Garner couldn’t breathe just for selling loosies. And then Alton Sterling was a threat just for selling CDs. And then Philando Castille got shot for reaching for his wallet. And then another…and then another…and then another.

And THEN my professors were still asking me to engage in hypothetical analysis on criminal procedure exams while people were LITERALLY getting away with murder. As if we were living in two different worlds, business continued as usual while my concepts of a justice system and whether laws even mattered—let alone black and brown lives—were shattered.

While students of color were forming coalitions, and writing open letters, and marching in the streets, time after time, police shooting after police shooting—chanting hands up don’t shoot and begging people to say her name—the rest of the university, with the exception of a handful of amazing rogue, tenured professors, largely said nothing (read: thoughts and prayers).

And by THEN I had started to question why I went to law school in the first place. And this torturous reckoning continued until well after I graduated and took my first job. To be honest, sometimes if I’m not careful, it lingers still and taunts me: What was the fricking point?

…Of helping one client, only to have another judge who will continue to see black and brown boys as grown men before throwing the book at them. Of lifting the blockade out of another client’s way, only to encounter another prosecutor who will happily, and unconstitutionally advocate for my client’s incarceration because she’s poor and hasn’t paid her traffic fines. What good is my bar card, if the system, despite years of attorneys’ best efforts, largely remains intact, working as it was designed—as slavery by another name?

I think back on how “To Kill a Mockingbird” is in many ways a warning. A cautionary tale to young, aspirational lawyers who want to use their “powers for good,” that they can use every trick in their arsenal and evil can still win. So, what then, truly, is the point? The law often attracts those with big egos and big hearts. But when that ego is annihilated by a system that doesn’t care how strong your case is, that is designed to incarcerate, that can choose to ignore evidence you present—who are you then? Will you keep at it or will you crumble? I think that choice depends solely on why you’re doing the work, and I had to dig deep to find that answer.

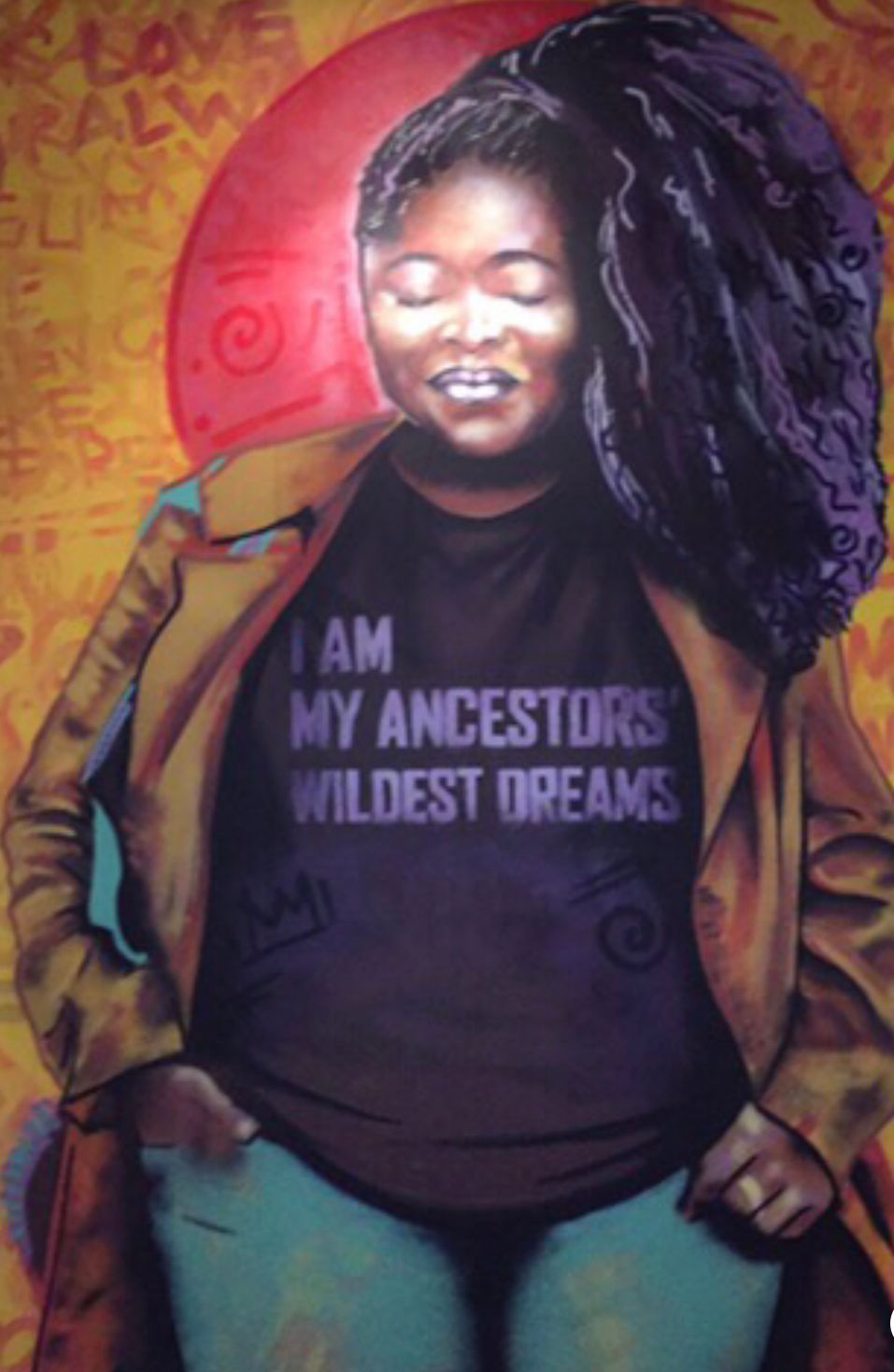

What I have learned through each day on this journey is that no matter how many times I want to quit, I have to find an inner resolve that what I am fighting for is bigger than one client, or one case. It is bigger than whether I win or lose. It is bigger than the money. I’d be lying to say those things don’t matter at all, but they don’t matter more to me than my people. It simply doesn’t compare.

In many ways, everything that gives me the stamina to do this work stems from my sensitivity—my own inner “mockingbird.” I am immensely grateful that despite the ugliness of our world, my mockingbird has not been killed, but it has instead been strengthened. A type of reckoning that allows me to fight through my tears, conquer my fears, and enter a courtroom prepared to be scoffed at and disrespected, simply for doing my job. The type that can hold space for a client that others have silenced or ignored, because I can remember when people held space for me, and how it felt when they didn’t.

As much as I used to think of my sensitivity as a curse, I realize daily on this career journey that it is a rare and unique gift that I must treasure. Instead of trying to force it down, instead of trying to kill it, I must instead protect it with every fiber of my being. It is one of the single most important things I carry with me each day. It is what gives me my relatability. It is what gives me my sass. It is what gives me my fight. It is what gives me my tenacity. It is what gives me my authenticity. It is what gives me my fire. It is what gives me my optimism. It is what makes me a zealous advocate. It is what makes me care. And in today’s America, giving a f*ck is a radical act.

So yes, it is indeed a sin to kill a Mockingbird—but to trill a mockingbird? That is love. That is light. And eventually, that is liberation.

Appreciated this read?

Share and spread the word.

Follow the author on social media:

@TheErinKeith

Comments