My Black Family's Migration Story: The Bold of Other Colds

- Erin Keith, Esq.

- Feb 28, 2021

- 6 min read

Updated: Mar 2, 2021

As I looked outside last week and watched the snow fall seven inches deep with temperatures sub-ten degrees, I found myself muttering under my breath, “ugh…why do I even live here?”. The Michigan weather, like that of many other Northern or Midwestern states, will certainly make one contemplate one’s frigid existence at least once every winter.

But as Black History Month comes to a close, I stopped to reflect on that thought and the trajectory that brought my ancestors to inhabit Detroit, Michigan. Why did they even come here? It struck me then, as it does now, how great a sacrifice they made to leave their immediate families behind to pursue a better life away from the horrors of Jim Crow. The choice to leave the familiar red clay of the South for the foreign snow of the North could not have been an easy one.

For instance, both of my maternal grandparents had humble beginnings, growing up on farms and working the land in Athens, Georgia. My maternal grandmother, the oldest of 18 children, lived in a small wooden home her father built with his own hands and had various responsibilities in caring for her younger siblings. My maternal grandfather, the oldest of eight, had a similar homelife nearby, and grew up picking cotton, corn, peanuts, and potatoes, while driving trucks as a teen, to help his family, before being drafted at age 18 into the U.S. Marines. When my grandfather returned to the segregated South from the service, he and my grandmother married in 1948. Against the odds, my grandmother obtained her cosmetology license after graduating from Cannolene Beauty College in Atlanta that same year. My grandfather similarly pursued advanced studies using the GI bill, and graduated from the Atlanta College of Mortuary Science in 1949, receiving his mortuary certificate and beginning a mortician apprenticeship. But, after having their first child and choosing to move North to escape the limitations of racism, the couple had to give up many of their own professional goals and dreams for the sake of migrating.

When my grandfather first came to Detroit to make money in the auto plants circa 1950, he left his wife and child in Georgia, while he worked to gain security. The couple chose Michigan because my grandmother had other extended family, including her own grandmother, who had already migrated to the area in the years before. My grandfather eventually sent for "his bride" and daughter and they came up on the train in 1951, with just the belongings they could carry. Once the family settled in Detroit, they lived on Conant St., eventually moving into the Sojourner Truth projects, after having their second child (my mother) in 1953. When my grandparents tried to pursue their original career paths, they were informed that their respective studies and licensures were deemed invalid, and were told, to their dismay, that they’d have to do them all over again. With more pride than money, my grandparents adapted their plans, all the while instilling in their children the value of a dollar and the value of education.

My grandfather left his work on the line at auto plants to begin work as a mail truck driver for the post office, progressing to a tractor trailer driver as he acquired additional skills. He eventually retired as the superintendent of vehicle operations, after a postal career in vehicle services that spanned more than 34 years. While my grandfather worked his postal job, along with several others, my grandmother was a devoted homemaker who contributed to the family by doing hair for customers out of her home, selling Beauty Counselor brand makeup, and working other jobs to make ends meet. Because of their sacrifices, they eventually owned multiple properties, including three homes in the Aviation Subdivision they had previously helped to integrate. They also raised to two intelligent daughters who were able to obtain higher education. In fact, my mother was valedictorian of her high school class, went to college on scholarship, attended law school at night while working full time, and went on to become the first lawyer, and later judge, in her entire family.

My paternal grandparents had their own migration story. My paternal grandmother grew up in Lebanon, Tennessee, with her five siblings on a dirt lane ironically called Africa Road. Many of her relatives also resided on the same street and so the family of aunts, uncles, and cousins, very much lived together as one village. After teaching for years in a one-room schoolhouse, my grandmother moved to Detroit in the 1940s to work in the “war plants” during WWII, living with her brother and his wife who had already migrated. It was there that she met my paternal grandfather, a man who stopped at the home where she was staying, while selling real estate through his father’s business, P.A. Keith and Sons.

My paternal grandfather had migrated to Detroit as a child with his father, stepmother and three younger siblings. My grandfather’s biological mother passed during childbirth and my grandfather was born 20 minutes after she was pronounced dead. The decision could not have been easy for my great-grandfather, the child of slaves turned serial entrepreneur who owned a barbershop, restaurant and multiple properties in Atlanta and who helped to found the Atlanta State Savings Bank, to leave his home in the late 1920s to move to Detroit to work in the auto plants. However, his decision to remarry, to move North, to have five children, to start his own real estate business as a Black man in Michigan, and to raise his children to be strong, self-sufficient, and proud, changed the trajectory of his descendants’ lives. His youngest son, for example, went on to become a federal judge on the U.S. 6th Circuit Court of Appeals.

After my paternal grandparents' fateful meeting, they married 1945. My grandfather worked as a postal clerk sorting the mail, while my grandmother was homemaker, who bore four children. During his time at the post office, my grandfather also founded the United Committee on Negro History in 1956, an organization celebrating Black achievement and holding large-scale programs each year at a local university during what was then called Negro History Week. While juggling the roles of wife and mother, my grandmother sold makeup for a company called Studio Girl, and later worked as a payment clerk at the Wayne County Friend of Court until she retired in 1975. Despite their humble beginnings, my paternal grandparents raised four college educated children: a federal human resources manager, a journalist (my father), a judge, and a PhD.

Many Black families have stories of their families leaving the South to escape racism’s grip, to journey North towards new opportunities and a renewed hope for prosperity. When talking casually with a good friend of mine, she recalled her family’s migration story: her father’s family fled North after her paternal grandfather in Alabama was tied to a bed, beheaded with a power saw, and their family home was burned to the ground by a white mob. Such heinous actions were purported punishment for a local white businesswoman having a crush on my friend’s married grandfather, to which he was not receptive. It is important to recognize that these stories of horrendous trauma and tragedy are not just relegated to history books and are not old news. These oral histories live on in Black folks’ current, breathing descendants whose lives have been forever impacted by both the racism our ancestors experienced, and the resilience they were forced to display through migrating North.

Author Isabel Wilkerson chronicles the Black families’ migration narratives in a book appropriately titled, The Warmth of Other Suns. But as I reflect on my own family’s legacy, I think of my ancestors’ willingness to choose the bold of other colds—the cold climate of Detroit and its own version of Northern racism, over the cold, often deadly, realities and legal limitations of the South under Jim Crow segregation.

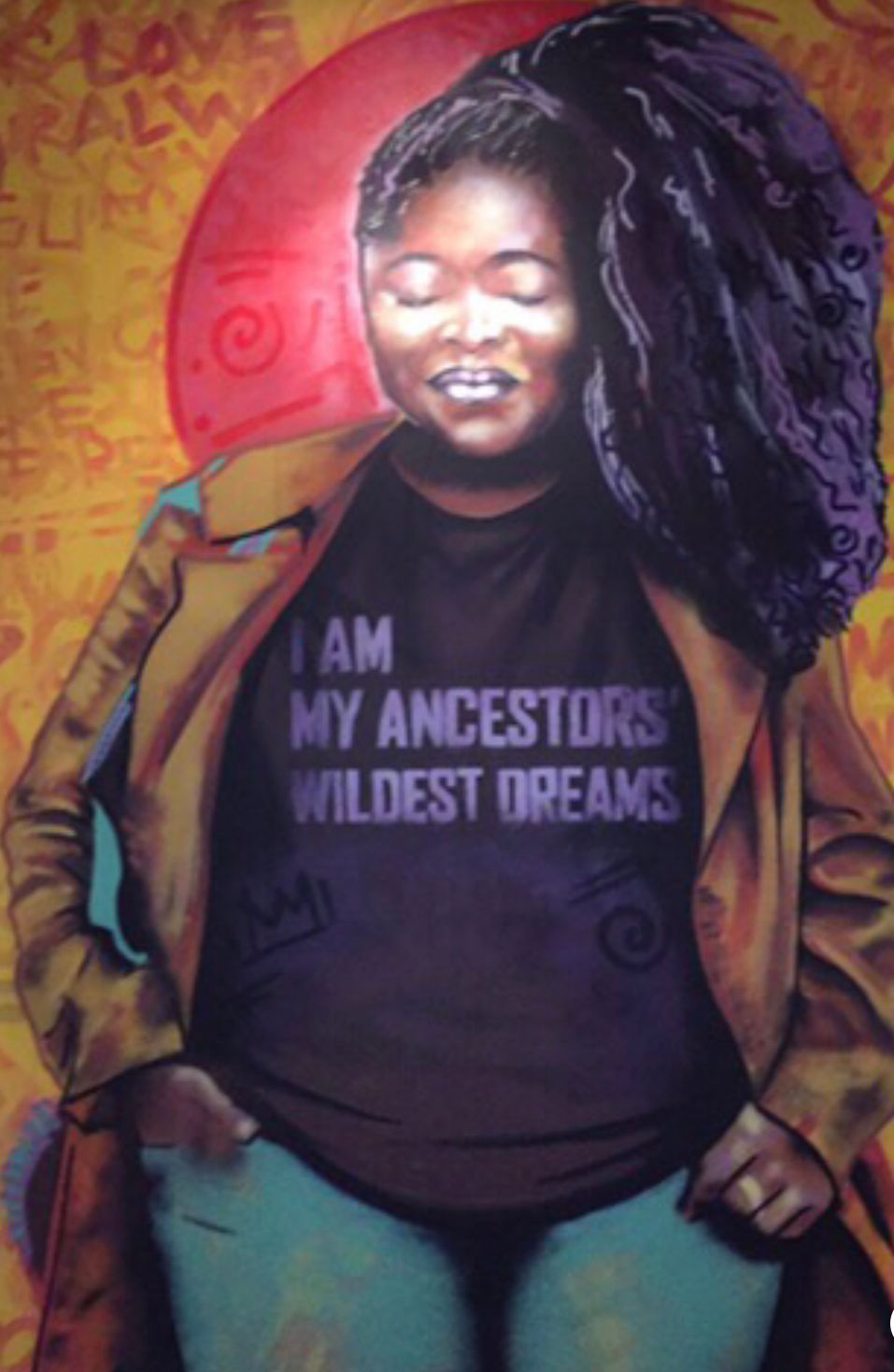

In choosing the bold of other colds—and because of their immense sacrifices—my ancestors made it so that I could write this blog as a college educated, third-generation lawyer and second-generation writer, on my couch from my living room in Detroit, Michigan. They made it possible to have so much abundance and self-determination and self-sufficiency and education and tenacity and pride and excellence on my family tree. And while my family who remained in the South was uniquely successful and resilient in their own right, I am forever awed by and indebted to my bloodline who sought something different for their children, even against their own immediate interests.

When I think of immigrant stories today, of those who continue to come to this country hoping for a better life, I spiritually and emotionally link arms with them, in remembrance of my own ancestors who dared to dream. I think of all that my grandparents gave up on their respective journeys—the businesses, the degrees, the titles, the proximity to parents and their extended families—and all that they gained by being brave enough to seek out something foreign by faith alone.

It is for this reason that I have a new appreciation for Michigan winter and for the snow that falls outside my window. I will carry this appreciation with me, even when it’s not Black History Month. The frigid temperature is a reminder that my ancestors’ sacrifices and their decision to choose the bold of other colds, was not in vain because I'm alive to feel its success in every wind gust. I encourage everyone with living relatives who might remember their families' migration stories to ask them questions the next time it snows. As for me, each time I bundle up and brace for the cold, I will do so with gratitude.

Appreciated this read?

Share and spread the word.

Follow the author on social media: @TheErinKeith

Comments