The Girls Aren't Alright: The Importance Of Keeping Our Sisters Too

- Erin Keith, Esq.

- Oct 8, 2018

- 4 min read

Updated: Jul 19, 2020

When I heard the news about the slaying of 18-year-old Nia Wilson as she boarded a BART train in Oakland, California, I was devastated; at a true loss for words.

For those of you who missed this terrible tragedy amid the seemingly constant attacks on black lives, in July of 2018, a crazed white man approached Nia, and her older sister Letifah, as they prepared to board the BART train, with their other sister, Tashiya. Only seconds later, without warning, the man brutally slashed Nia's throat and stabbed Letifah in the neck. Tashiya, who had just stepped into the metro car, looked back and saw pure horror. Letifah held their baby sister in her arms, as Nia bled to death on the platform. While Letifah ultimately survived her injuries, one can’t even begin to imagine the unfathomable trauma of this attack— something both sisters, and their entire family, must live with forever.

The white man who allegedly committed this heinous act, John Lee Cowell, was apprehended a day later and was subsequently charged with murder and attempted murder. Only time will tell whether he will actually be convicted and sentenced. Until then, we remain vigilant, and cautiously confident, that justice will prevail.

In the days following Nia’s passing, I couldn’t stop thinking about the effect this incident would have on my mentees— girls who much like Nia, rely on public transit to get to their destinations safely.

As a youth-justice attorney, I frequently interact with with brown and black girls through advocacy workshops, where they are encouraged to share their views on social injustices and ways they can use their power to fight back. No matter which group of young people I speak with—their city, their neighborhood, their socio-economic status—somewhere during the dialogue about the experiences of Black women and girls, a familiar preface or disclaimer emerges:

“…but, I mean, really, we don’t have it as bad as Black boys do.”

“We do go through a lot, but Black boys…they have actual targets on their backs.”

“We need more mentors and programs for us, but they really need mentors.”

“It is hard for us too, but we can’t be out here being weak.”

“The police don’t mess with us as much and try to lock us up as much.”

“Our targets don’t look like us getting killed everyday the way theirs do.”

While I hear the critical consciousness and important commitment to championing black boys that is present in these statements, I also feel a bit of heartache. As I do my best to reassure, and empower, and encourage, I can’t help but think about the very real challenges Black women face and the messages we send Black girls about naming their own plight; the discomfort and shame we inadvertently teach girls from birth about prioritizing their own fight.

I think of the little sisters that are sent home from school for skirts that are “too short" and natural, protective hairstyles that are “too distracting.”

I think of the little sisters that get flipped out of their desks by officers at school or kneeled on at pool parties.

I think of the little sisters killed by stray bullets, like Makiyah Wilson, Saniyah Nicholson and Taylor Hayes, in June and July of 2018 alone.

I think of the little sisters we’ve lost to over-policing, like Sandra Bland and Korryn Gaines, and the girls without a hashtag.

I think of sisters stolen from us by cross-racial violence like, Renisha McBride, and now, Nia Wilson.

And I think of the fact that Black women experience the highest rates of homicide of any racial group in the United States.

I worry that sometimes we are so overwhelmed with trying to lift the targets off our brothers' backs—to rightfully help them fight the many injustices they face—that we don't gives ourselves, or our little sisters, the permission to acknowledge the targets on our own bodies.

Our leaders spearhead amazing “My Brother’s Keepers” initiatives. National organizations create fantastic Black male excellence campaigns. Our foundations support vital scholarships and programs for Black male achievement. But… what of our Black girls? While we should absolutely create programs and provide resources to support our Black boys, what message is sent to our Black girls when comparable programs aren’t offered in their communities to address their trauma, their education gaps, and the violence they experience?

I also worry that in attempting to empower our little sisters, we teach them superwoman syndrome, disguised as community uplift.

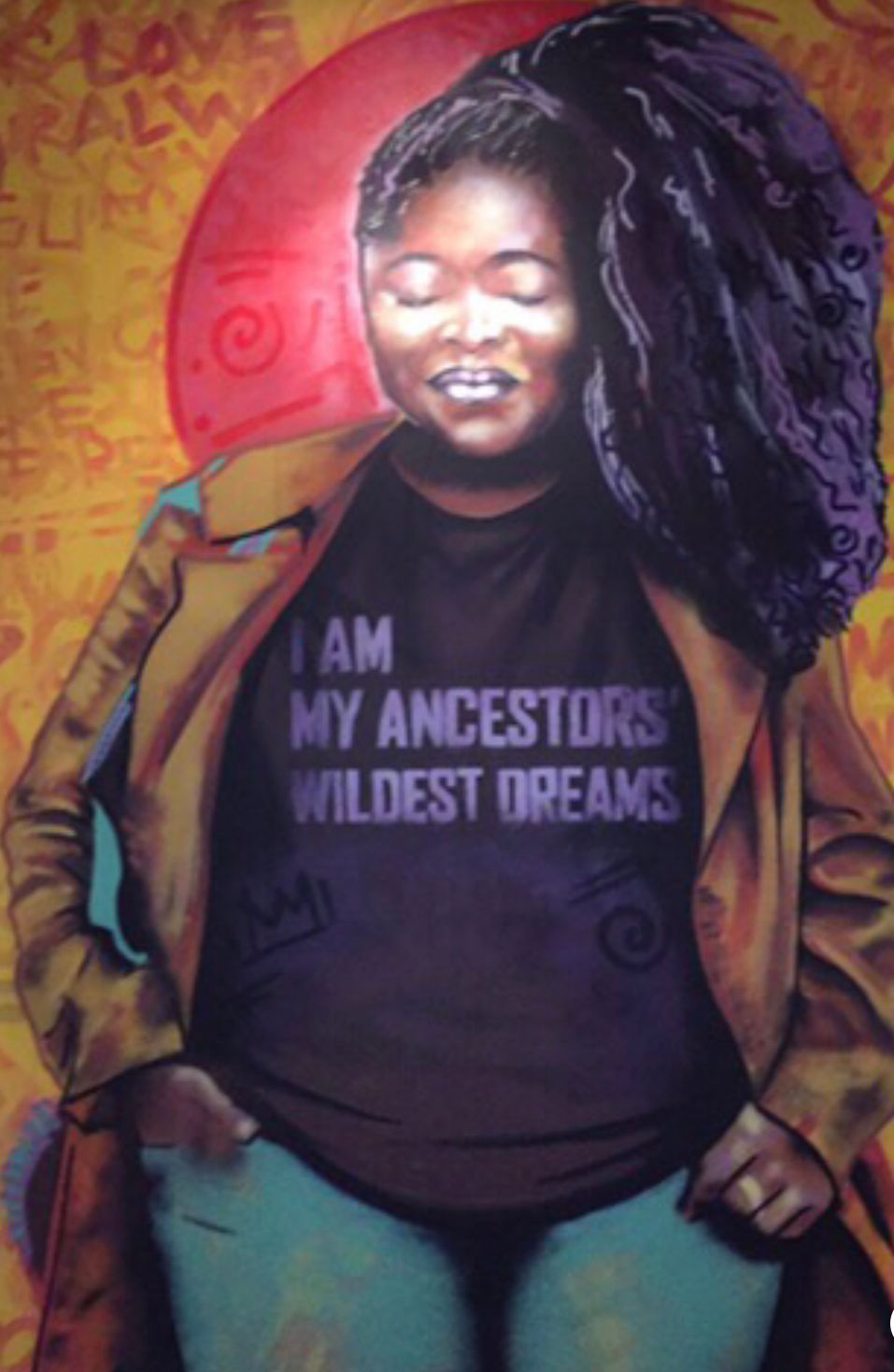

“Black Girls Rock.” “You are strong.” "You are powerful." “Black Girls [have] Magic.”

But what about the days they’re not feeling so magical? Do we give them room to be little girls? To be scared? To be fragile? To be hurt? To acknowledge the targets on their own backs, without being considered “weak"? Do we give them a moment to grieve for themselves, and not just for their brothers?

In the wake of Nia Wilson’s death, I encourage you to #SayHerName, but then, to go check on the Black and brown girls in your own community. Who roll their necks and pop their gum and act like they’re alright. Who give the disclaimers. Who might be quietly mourning a girl named Nia they didn’t know. Who might be silently crying for the cousins and sisters and mamas and aunties, lost to various forms of violence against black women and girls in our community. Who are grieving for themselves.

Allow them to name their goliaths, while working to strike them down. Allow them to admit that the girls aren’t alright, while working with them, and fighting along side them, to change this reality.

Note: A version of this article was published in October of 2018 on www.divineenthusiast.com.

Appreciated this read?

Share and spread the word.

Follow the author on social media: @TheErinKeith

Comments